Mastering The Learning Curve: How To Learn Fast And Effectively

This is the standard learning curve - which shows the relationship between practice and proficiency in any given field. In the beginning stages of learning something, performance rapidly improves. After time, practice yields diminishing returns, and progress solves down.

Examples of the learning curve

Take the chess rating progression of world champion Magnus Carlsen as an example: in the early 2000s, his proficiency increased rapidly and increased his rating by 400 points in three years, whereas in the following decade his rating progression slowed down. And his rating only increased 50 points in three years. This is an example of the standard learning curve. Beginning progression is fast, but slows down over time.

Labeling the learning curve

The standard learning curve misses one important thing: values on each of the axes. That is to say, how much time do you actually need to practice in order to achieve a certain level of performance.

Malcolm Gladwell: 10 000 hours to mastery

Let's start with one of the most famous claims regarding this subject: “It takes 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert or master in any given field." This claim was popularized by Malcom Gladwell, in his book outliers: the story of success. He backs his claim by examples such as the following:

- The most accomplished of the violin students at a music academy in Berlin had put in 10 000 hours of practice by the time they turned 20

- He estimated that the Beatles put in 10 000 hours of practice in the early 1960s

- He estimated that Bill Gates put in 10 000 hours of programming work before founding Microsoft.

Tim Ferriss: 500 hours to world class

Furthermore, we can consider the claims of Tim Ferriss, author of the 4-hour chef, who states that you can become world class or better than 95% of the population in 6 months or less. He doesn’t specify the amount of hours required, but using some quick estimations and napkin math, it can be approximated to around 500 hours of practice.

Josh Kaufman: 20 hours to learn

And lastly, Josh Kaufman, in his famous TedX talk, emphasizes the first 20 hours of practice, as being sufficient to be “good” at anything. He wrote about this in his book titled "The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything … Fast"

Variance in the learning curve

The above graph does not tell the full story at all. A major problem with the graph is that it varies greatly from person to person. One person's learning curve may be steeper, or more gradual, or have a lower starting point, or a higher peak. For example, the peak rating of one of the best Go players in the world, Ke Jie, is going to be much higher than the majority of people.

Moreover, a single person's learning curve may be different from skill to skill. One person may progress fast in chess, but struggle to learn skateboarding. For another person the opposite may be the case. Rafael Nadal probably has a better predisposition to playing Tennis than solving Rubik's cubes.

Going back to chess; Psychologists Fernand Gobet and Guillermo Campitelli found that there were actually huge differences in the number of hours of practice it took chess players to reach a “master” status, ranging from 728 hours to 16,120. This would completely change the earlier learning graph, as the 10,000 hour data point may be moved to as low as 728 hours, or instead to as high as 16,128 - both of which are vastly different from the 10 000 rule.

Nature vs. Nurture in learning

The time it takes to learn the basics of any skill varies greatly from person to person. The reason why this is the case, is that learning environments differ, and there are great differences in individual biological predisposition to learning. There has been research done on the relationship between skill acquisition and genetics.

As an example, twin research led by Robert Plomin at King’s College London had more than 15 000 twins in the United Kingdom perform a series of tests to test drawing ability. Identical twins’ drawing ability was much more highly correlated than fraternal twins’ drawing ability. Since identical twins share 100% of their genes, whereas fraternal twins share only 50%, these findings indicate that differences between people in basic artistic ability is at least in part due to genetics. Using the same data set, over half the variation between skilled and less skilled readers was found to be due to genetics. Clearly, the number of hours two people will need to put in to master a skill will be different depending on their genetic disposition.

Taking a step further, some research indicates that there are skills which are entirely controlled by genetics, and cannot be improved with practice. Psychologist Miriam Mosing of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden has conducted experiments in which practice had no effect on skill improvement. In her research, identical twins who regularly practiced music, were not more likely to be skilled in basic music abilities such as judging whether two melodies carry the same rhythm. Instead they found that genes influenced 38% of measured musical abilities. This is not to say musical abilities cannot be improved, they certainly can and there are musical skills that you can improve with practice. However, the research does indicate that genetics play a big role in musical skill and that there are limits to the power of practice.

On the other hand, there are aspects to performance which have been thought to be entirely genetic for a long time, but have now been proven to be influenced by training and practice. As an example, it was long believed that it isn’t possible to voluntarily influence our own autonomic nervous system, especially the innate immune response of our bodies. Researchers at Radboud University had 12 healthy participants train for 4 days under guidance by Wim Hof, of which all of them managed to voluntarily influence the innate immune response - expanding the scope of what experts thought was possible through practice.

Running a mile in under 4 minutes is considered one of the holy grails of athletic achievements. In 1940, legends say that even experts thought such a feat would be impossible, or that it would require perfect conditions in order to achieve. Since then, over 1400 athletes have done it, including high-schoolers.

These are two examples of people expanding the scope of what is thought to be possible through practice and training. These are arguments for humans being a lot less biologically limited than we may think we are.

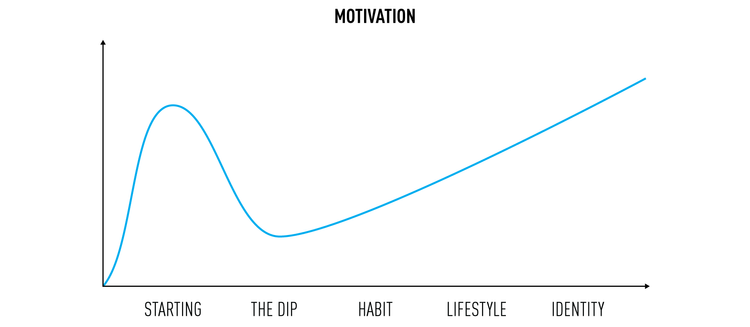

Managing motivation while learning

As I have written about in my motivation masterclass, motivation tends to follow a curve. Motivation is high in the beginning, as progress is fast and proficiency rapidly increases. However, the key thing to notice with regard to the learning curve, is that motivation tends to take take a dip as progress initially slows down. And indeed, skill acquisition will generally become slower and slower from here on out. The important thing to be aware about, is that motivation will again continue to rise.

Conclusion

In conclusion, nature and nurture interact to create expert performers. Any healthy individual has potential for expertise. Though genes and training may set the physiologic limit, it is behavioral and other factors that determine the ultimate frontiers of human performance. All humans follow a similar learning curve, whereby we progress fast in the beginning, but over time, progress slows down.